The C.F.Monroe Story

Copyright Wilfred R. Cohen

(As originally written by R. Shawn Bradway in the mid 1970’s)

The C.F. Monroe story is one of the many Cinderella stories of modern day collection. Until recently this fine glass was amazingly neglected: amazingly since it easily rivals similar articles produced by the Smith Brothers and Mt. Washington Pairpoint Glass Companies in nearby New Bedford, Massachusetts. However, while the demand and the prices began to rise for the various decorated Opal Ware articles produced by Mt. Washington and the Smith Brothers, comparable C.F. Monroe pieces often sat unnoticed on the shelves of many antique shops. All this irrevocably changed when Albert Christian Revi, author of Nineteenth Century Glass, and other authors began to call collectors’ attention to the fine qualities of this lovely glassware. The fire of collector enthusiasm was ignited, and prices began a dramatic rise.

Decorated Opal ware was at the height of its popularity from 1890 to 1910, and the C. F. Monroe Company was one of the largest producers of this type glass. Charles F. Monroe opened his shop first shop in 1880; is was located at 36 West Main Street in Meriden, Connecticut and he dealt primarily in imported glassware. By 1882, Monroe was operating his own glass-decorating studio, and was soon employing highly talented local artists as decorators. When the 1890’s arrived and the demand for finely decorated glass was its height, the Monroe company was located in several large buildings on the corner of West Main Street and Capitol Avenue, and employed such fine artists as Carl V. Helmschmied, Walter Nilson, J.J. Knoblauch, Joseph Hickish, Carl Puffee, Flora Fiest, Gustave Reinman, Florence Knoblauch, Emil Melchior, and Alma Wenk, Blanche Duval, Gussie Stremlan, Elizabeth Zeibart, and Elizabeth Casey, The decorators often went back and forth between the companies, and sometimes poses a problem of attribution. As is always, the case, public tastes changed, and the demand for decorated Opal Ware began to decline after 1910. The C.F. Monroe Company went out of business in 1916.

The Monroe Co. did not manufacture its own glass; rather, it bought its blanks, i.e. undecorated glass, from France, Mt. Washington-Pairpoint and possibly other American glass houses. (One, I was told in personal communication, was Roedifer Glass Co, Bel Air, Ohio. Ray Menendian of Columbus, Ohio, now deceased knew the son personally. The son had some pieces decorated by C.F. Monroe on glass made of Roedefer.) These glass blanks were of an opaque, creamy white glass called, by the trade. Opal Ware. While the majority of these blanks were made in a mold and the mold lines may be detected on the finished product, pieces have been discovered without any mold marks. I don’t think it was ever blown. It is interesting to note that some of the glass, such as the Helmschmied swirl was designed and patented by C.F. Monroe Co. What we now refer to as the egg crate of puffy piece, actually called Billow Ware in the catalogue, as well as the blown out flowers, are unique to C.F. Monroe, as is much of the other glass blanks they used. One can infer that they must have designed the glass, and had it made for them and did not just decorate what was made at the time. It is unusual to see other companies use the same blanks and decorate them.

Before the blanks were decorated, a large number of them were treated to an acid bath of some type; this gave the blanks a soft, lusterless finish. Many of the blanks that were not acidized had a matte surface painted on with the background color. Several acidized pieces have been found with a glossy background color painted on all or part of their surface; these are scarce. Very few pieces were left in their original glossy state.

In C.F. Monroe, the decoration is EVERYTHING. As noted above, there is little art in the glass itself although many of the pieces have interesting and varied shapes. The decoration is mostly very characteristic. Once in a while, a complete surprise comes up. The decoration came in at least seven categories or ‘Assortments’, as the company called it. The intricate the design, the more costly the charge from the factory, and indeed, the more they are worth today. Some of the finest pieces are possibly done in limited numbers and there may have been special orders. The 1900-01 catalog states, ‘any change from our regular line of stock goods will have to be submitted to the factory, and special prices quoted’.

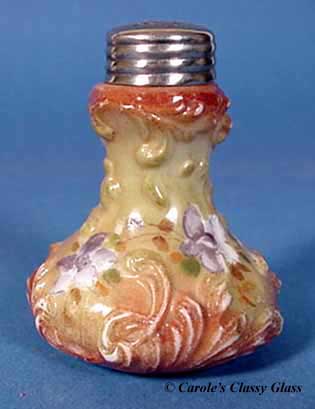

In the decorating process, the majority of the blanks was first entirely or partly painted with one or more background colors in pastel pinks, blues, yellow, and ivory, in rich tones of sage green, apricot, royal blue, and rose, and even in such rarely used colors as purple and black. Some of the skillfully blended colors resemble the earlier Peachblow, Burmese, and other shaded wares; in fact, one combination of pink and yellow so resembles Burmese that it is called ‘Painted Burmese’, and is eagerly sought by collectors. While the background color was being applied, the area which was to be additionally decorated with floral and other motifs had to be kept free from color. This was probably accomplished by applying some type of wax to the design area before the background d color was applied. When the background color was fired in the kiln, the wax was burned off, and the area was ready to be decorated.

After the background color was fired, the various motifs were painted on with acid-reduced enamels, usually in delicate colors, and again fired in the kiln. Finally, raised enamel (frequently white), coin gold, enamel and gilt, and raised gold accents were added; this required yet another firing. Those several firings combine with the right artistry, the elaborate decorating techniques, and the fragility of the glass (many pieces were undoubtedly destroyed in the firing process) served to make much of this ware comparatively costly when it was sold.

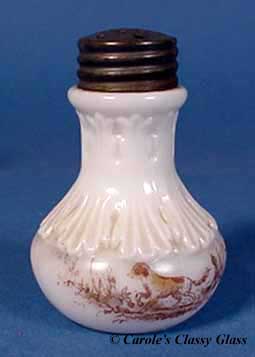

Floral decor is that which is most frequently encountered on Monroe pieces. Also found are pieces with portraits (especially of Queen Louise), cherubs, and leaf designs. Relatively scarce and in great demand are pieces with seascapes, landscapes, animals, birds, courting couples and geometric, Persian-like, beaded designs. As mentioned previously, all the various motifs were further embellished with white beading, raised gold, lavender scrolls, etc. The total effect was exceedingly rich, bringing to mind the rococo and baroque eras in art.

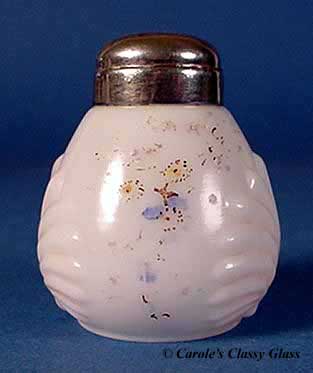

The C.F. Monroe Company turned out its decorated Opal Ware in a variety of forms. Undoubtedly the most popular was that of a covered, hinged box, and these boxes are found today in an infinite variety of shapes and sizes, which include jewelry boxes, oblong glove boxes, etc. Some of these items are in excellent condition and still have the original linings. In addition, today’s collector can find Monroe items in such forms as vases, bowls, biscuit jars, pin dishes, cardholders, letter holders, etc. Scarce items include sugar sifters, napkin rings, paper weights, whish broom holders, pin jars, wig holders and blotters, etc. Monroe items, although decorative, were meant to be used. T his may be the reason why so few Monroe pieces still exist – they were used, got tarnished, or broken and thrown out.

The majority of Monroe pieces may be divided into three main categories; Wave Crest, Nakara, and Kelva, and pieces may be found with one of the other of these three signatures. Many of the pieces were never signed, especially some of the finest pieces. Monroe frequently stated his belief that the glass ‘spoke’ for itself, and needed no signature. Wave Crest was the first on the market, and enjoyed the largest and longest period of manufacture. Although Wave Crest is generally found with pastel backgrounds and on blanks with elaborate embossing, articles with dark colors and pieces with perfectly plain blanks are occasionally encountered. Wave Crest used a lot of flower transfers, and occasionally scenes and cherubs, etc. They then colored over them, also adding thick enamel touches to make them look hand done. However, it is felt that most of the transfer work came late, when the company tried to save money before it folded. I can only find one transfer piece in the 1900-1901 catalog, page 82, 12-6x. If they made more at that time, they certainly didn’t advertise the fact. Wave Crest is found in a much wider variety of shapes and forms than either Nakara or Kelva.

More scarce than Wave Crest, Nakara is frequently found in quite simple shapes with deep, rich background colors accompanied by beaded and raised enamel rococo scrolls. Beading is a characteristic of Nakara, although sometimes a mixture of beading, Nakara pastel background, and Wave Crest decoration appear on one item. Although Nakara is usually found with an acid finish, pieces may be encountered with a glossy surface; these are quite rare. Transfers of portraits, scenes, Gibson Girls, and Kate Greenaway figures are extensively used in Nakara pieces. These are quite beautiful, and command high prices. Occasionally portraits and scenes are fully hand decorated.

Apparently very little Kelva is generally found in simple shapes; it is always found with its unique, mottled, batik-like background (probably produced by a sponge or crumpled rage dipped in enamel). While Wave Crest and Nakara are found with all types of motifs, Kelva pieces are almost always found with floral decor. Occasionally, the same blank was used for all three types, and of course there are many exceptions to the above generalizations.

In addition, Monroe produced four other categories of decorated glass. One is a type of decorated crystal glass with enamel stained background quite similar to, and frequently mistaken for Mt. Washington Royal Flemish and Verona in the finest pieces. Monroe’s Decorated Crystal Ware may be found in the same shapes and with the same decor as the Opal Ware pieces or may be found in entirely different shapes and entirely different decorations. Quite a few of the Decorated Crystal Ware items have the raised white beading found on so much of the Opal Ware. When signed, these pieces have the Wave Crest black mark signature.

The second type is a decorated Opal Ware quite similar in coloring to Nakara, but with bisque-like china flowers applied to the glass. Very rare pieces with both portraits and applied flowers can occasionally be found; these are generally of exceptional beauty, and are usually signed Nakara.

Like Mt. Washington, Monroe produced some pieces, which could be called Blown-out Opal Ware, and this is the third type. Essentially, some part of the blank is so raised as to appear blown-out like the Pairpoint lamps of that name. On some Monroe pieces, the blown-out portions were enameled in such a way as to accent their raised position. The Monroe Company turned out unusual small boxes in which the top was almost entirely covered by an exquisitely tinted, blown-out flower. These blown-out pieces may be found with one of Monroe’s identifying signatures in all three lines.

The fourth is Wave Crest Cameo. The opal ware boxes were cut back with a pattern and then painted to outline the design. The bottom half of the box was also cut to finish out the design with the top. These boxes were cut back with a pattern and then painted to outline the design. The bottom half of the box was also cut to finish out the design with the top. These boxes are exceedingly rare.

Many Monroe collectors are not aware that the C.F. Monroe Company produced cut glass. Around the turn of the century, they produced some of the finest cut glass in the country; unfortunately, very few pieces were marked. However, Monroe cut glass boxes can be easily recognized because they generally take the same shape and have the same collars and clasps as their Opal Ware counterparts. Even less well known is the fact that this same company manufactured some beautifully embossed sterling silver and brass boxes. Now and then an article of cut glass with a marked ‘sterling’ part and occasionally, signed with ‘C.F.M. Co.’ or trademark will come to light.

Once in a great while, a piece of finely decorated china will be discovered bearing the signature of some Monroe artist; it is highly doubtful that these pieces were production items. These china pieces frequently have the same type of decoration as found on Wave Crest and include cake plates, dishes, ash trays, etc.

The majority of Monroe articles are found with silverplated or ormolu metal parts attached to them. Some pieces have brass parts and these can sometimes be found with ‘CFM Co.’ signed on the piece. While ormolu parts are found on a majority of the items, silverplated parts are usually found on table items such as biscuit jars, sugar sifters, salt and peppers, etc. and on quite a few of the Kelva pieces. The metal parts were attached to the glass with plaster of Paris. (When making any repairs, do not ever attach them with any form of glue. They will never come off again!)

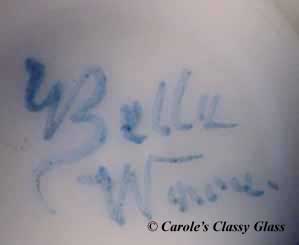

In conclusion, a few words should be given to the ‘problem’ of signatures. While many of Monroe’s most commercial pieces were signed, a large number of the finest pieces, especially in the Wave Crest line were not signed. (they may have had paper labels). These unsigned beauties have far greater aesthetic worth and eventually will have a far greater value than the simple, signed pieces. I have often seen collectors leave a beautiful piece because it was unsigned. In my opinion, the signature is totally unnecessary in 99.9% of C.F. Monroe glass, and does not make the piece worth more or less. The glass and decoration are usually so distinctive, to even the early collector, that it can easily be recognized as a piece of C.F. Monroe. For those who are unsure, I can only say, as in all fields of collecting, get to know your subject. Rarely, in my experience, but once in a great while, items with forged signatures appear, usually with the banner mark, and this should serve to further discourage an over-reliance on signatures. The forged mark will usually wash right off. Finally, there is no evidence of one signature being any earlier than the other. As Monroe himself believed, his glass does speak for itself, and no serious student of glass needs a signature, true or otherwise, ‘early’ or ‘late’, in identifying the elegancies produced by this fine company.

A word on identification; Sometimes, I am not sure if a piece is C.F. Monroe. If you are not sure, make the seller justify their attribution. It’s not enough for them to say ‘If you’ve handled as much glass as I have over the years,’ etc. That doesn’t explain anything, and proves nothing except that they really don’t’ know. Most reliable dealers are eager to help by discussing the pros and cons of obscure pieces, and especially will admit if they are in the dark about an item. None of us know it all, and we stand to learn a great deal from each other.

A final note; Not all opal glass, with or without rococo was Monroe, Some of the pieces confusing to novices are other manufacturers’ forms of Opal Ware, probably Belle Ware, Handel or Keystone Ware and not necessarily Monroe. As stated elsewhere, and I feel it is so important, that I feel it is necessary to repeat; the signature is unimportant in making a decision on whether or not to buy a piece of C.F. Monroe. ‘IT DOES NOT ADD TO THE VALUE’. The value is based on the quality of decoration, and of course, the rarity.

NOTE: Within an associated article in this website section are pictures of C. F. Monroe salt and sugar shakers that are owned by members, have appeared in familiar Victorian glass publications or, most recently, the April 2010 issue of The Pioneer. Many thanks to Wilf Cohen for permission to include this article in our website.