Salt Shakers That Do Something!

by Marilyn Lockwood

(Reprinted from the April/May 1990 “Glass Collector’s Digest”, Volume , Number . Marilyn Lockwood was a member of AAGSSCS from its inception until her death in 1998. She wrote many articles for The Pioneer on shaker identification in her column, “Scribbles from a Salt Shaker Student.” She was the first president of our club and she and her husband, Chub, hosted the first AAGSSCS convention in Hornell, NY in 1986.)

Have you ever thought there ought to be a better way to do something? Have you said to yourself that you could make something better than what’s on the market: I remember when I was young that my father spent many winter evenings trying to discover the secret of perpetual motion. He believed that could be the answer to high energy costs. It is an old Yankee tradition to dream of inventing a better mouse trap or improving the quality of life.

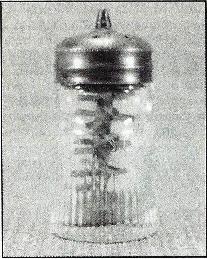

Picture a family dinner in their home over 100 years ago. Feather has just dented the cover of the salt shaker trying to loosen enough salt to flavor his potatoes and turnips. The children keep straight faces so as not to upset Dad Further. Later the kids finish their chores while Mother cleans up the kitchen. Father sits by a kerosene lamp, tinkering with an idea to get salt out of the shaker. Similar scenes must have occurred in many homes judging by the number of patents granted for agitators and combination shakers. The best known agitators, and probably most successful, were the Alden Christmas Barrel Salts (pictured first, below). There are at least two other shapes of Christmas Salts—the Christmas Pearl which is found in milk glass with typical Sandwich decoration (pansies, leaves, etc.) and three sizes of heavy clear glass in Waffle, Octagon pattern (Fig. 1). All have the patented Christmas Salt agitators in sizes to fit.

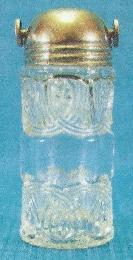

Figure a: Christmas Barrel salt shaker; Figure 1: Waffle, Octagon (3 sizes) and Christmas Pearl salt shakers; Figure 2: Little Owl salt shaker.

There were many additional wild and improbable ideas patented to pulverize the salt which contained so many impurities that it attracted moisture and became almost rock hard. Some inventions never reached actual production and the remaining ones are scarce to very rare today. Collecting them is a challenge but a rewarding one. We call them the shakers that don’t just sit there. They do something!

The name salt shaker or shaker salt came into general use in the 1890’s. “Shaker” had been recognized as a container in which to mix drinks, so its slow acceptance as a bottle for dispensing salt was understandable. Although salt shakers gained popularity from the mid-1860’s on, they were designated by a variety of terms such as dredge, cruet, sprinkler, bottle, distributor, etc. This accounts for the names used in the patents. My grandmother always called them salt cellars and assigned me the chore of poking clear the perforations in their tops with a toothpick.

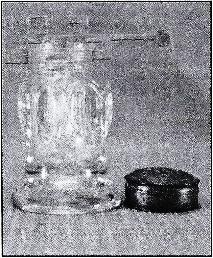

I believe salt shakers were in general use much earlier than we’d imagine because of the multitude of early patents granted to improve them. The earliest patented inventions (1863) came from eastern Massachusetts. By 1877, H. P. Pears of Pittsburgh had a patent for the design of a shaker, now called Little Owl (Fig. 2). Leon Lemos of San Francisco patented a dredge bottle in 1886. Obviously shakers were being used all over the country. One early castor bottle held a wooden agitator imbedded in a cork in its bottom and “rising through the center with a series of arms extended transversely through the stem in various directions.” It was meant to pulverize the salt when the bottle was shaken. Charles Crossman’s 1863 patent does not specify the material to be used, but the agitator pictured in Fig. 3 is wooden. Perhaps it was more substantial when new.

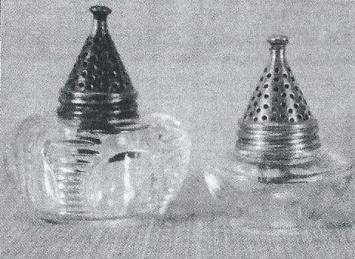

Figure 3: Pioneer Companion salt shaker; Figure 4: Richardson salt shaker; Figure 5: Haines salt shaker; Figure 6: Radient salt shaker; Figure 7: Coil Top salt shakers.

George Richardson was granted the first patent for an unattached agitator in 1867 (Fig. 4). A metal rod with points or projections at each end was to be shaken in the salt against a cork in the bottom which prevented damage to the bottle. He claimed this formed no stationary obstruction to the salt. As with some others the patent date appeared on the agitator and was embossed in the glass near the bottom of the bottle, although the patent was for the agitator.

John Haines received a patent in 1878 (Fig. 5) on a dredge bottle “to be blown in a mold in such shape that the interior is furnished with arms extending from the sides and/or bottom, said arms being integral with the bottle.” He claimed that this avoided all application of metal pieces “which are usually unhealthy and have a tendency to soil and color salt.” Again the idea was to loosen the salt by shaking it against the glass arms. One wonders if the salt of the glass pulverized. It is an attractive shaker with the projections forming star-like patterns on the outside.

Did you ever see a salt shaker with a “journaled shaft, a disk and sockets?” Those descriptive words appeared in the patent issued to Metellus Thomson in 1887 for a salt shaker called Radiant (Fig. 6). He states that the ordinary pepper-box salt cellars have perforations that clog, leading to difficulties that are “troublesome and annoying.” However, he claimed his invention solved this problem and that by proper turning of the shaft the disks would discharge any desired quantity of salt through the slots. I’m curious to know how expensive they were to produce.

In 1881 Thomas Brown patented a novel idea in a vibrator-type agitator, now called Coil Top (Fig. 7). It consisted of a “helix spiral wire cap” wound into a beehive shape with one end protruding vertically into the bottle. Salt would be loosened by turning the cap on the bottle or by depressing the loosely wound wire cover. Mr. Brown called it an “open cap” for bottles. That described its weakness also because the spaces were designed to dispense salt allowed moisture to enter and cake the salt. In spite of this, apparently quite a few were produced because they are found in clear glass and in milk glass.

Figure 8: Arched Oval salt shaker; Figure 9: Parker salt and pepper shaker; Figure 10: Ripley’s Combination salt shaker.

Figure 8 shows an interesting agitator in the Arched Oval pattern shaker. It fits through a hole in the bottom of the shaker and can be rotated from that end to scrape the salt loose. The gasket which must have sealed the bottom is missing. Charles Gilbert was granted a patent very similar to this. This method looks more efficient than many of the others.

There are several combination shakers of historical interest. One is called Parker (Fig. 9) for its inventor, Lyman B. Parker, who lived in Chickasha, in the Chickasha Nation, Indian Territory (Oklahoma). He received his patent in 1904 for a composite condiment holder. It has two compartments with a cap hinged to cover one side or the other to sprinkle either salt or pepper. The cap has projections which fit into the perforations of the side being covered, thereby unclogging the holes. The name Parker is included in the pattern on the glass. It works quite well.

Another was patented in 1873 by Daniel Ripley as an “Improvement in salt and pepper dredges.” (Fig. 10). A glass vial for pepper screws into a threaded socket in the cover and hangs into the main bottle which contains salt. The cover has a rotating cap which, when turned, opens one set of holes and closes the other set, allowing the user to choose either salt or pepper. This shaker is found in two sizes in clear glass and even in a ruby-stained Button Arches pattern, indicating it proved useful over many more years than most others.

Figure 11: Atterbury Twin salt shaker; Figure 12: Propeller salt shakers (two sizes).

Thomas Atterbury received a patent in 1873 and assigned it to Atterbury and Company to manufacture “salt and pepper dredges combined.” They can be found in clear glass and the distinctive Atterbury white opaque. This rare Atterbury Twin (Fig. 11) has a handle, is double chambered, and dispenses salt from one side of the pewter top and pepper from the other, depending on the direction it is tilted. Dexterity and experience are needed for successful dispensing.

We have collected others that contain variations of the loose agitators, propellers (Fig. 12), choppers or moisture absorbing cylinders. Then there are the elusive ones such as Chain Top which was advertised in 1881 by the Union Salt Castor Company of New York. Suspended inside from the top was a long chain which the company claimed would not be rusted by the salt. Their ad also states “It is against International Law to use chain shot, but we make a shot and keep the law by using a chain in our Castors.” We have not found one of these shakers but maybe next week…next month…next year?

So much of this information comes from Dr. Arthur G. Peterson’s books that credit and gratitude must be expressed. Dr. Peterson is Honorary President of our Antique and Art Glass Salt Shaker Collectors’ Society but is also esteemed by a much wider group of glass collectors as a meticulous researcher and as one who named many glass patterns. His name appears as a reference in most recent books on pattern glass. Dr. Peterson’s book, Glass Salt Shakers, 1,000 Patters, is the shaker collector’s bible as well as a general reference for pattern names. His Glass Patents and Patterns contains a wealth of information on patents and patterns of early glass, glassmakers, inventors, and more, with illustrations. In fact, this book won the 1972 award of The Philadelphia Patent Law Association. That makes it sound rather pedantic, but it is fascinating reading for any glass collector and student.

Salt Shakers are taken very much for granted today. Some people look incredulous and question the time we’ve spent collecting them. Just see what can be learned, not only about glass and patents, but about history and the ingenuity of our ancestors. When next you salt your potatoes, give a little respect!