Just Found – The “Real” Northwood Alaska Shakers!

By Bob and Carole Bruce

Harry Northwood made some of the most beautiful glassware of the Victorian era. Today it is highly collectible whether it is colored pattern glassware, custard glassware, or carnival glassware. One of the most sought after patterns and one of the most beautiful, in the opinion of many, is a pattern he named Alaska. It was introduced with a sister pattern he named Klondyke. As with several other patterns, they were named after people or events popular at the time. The Alaskan gold rush prompted these names. These successful table patterns were introduced in 1897.

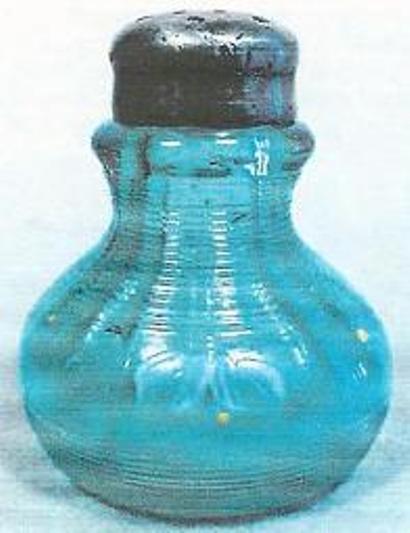

William Heacock noted that the Klondyke salt shaker (pictured below, right) was often used with the Alaska pattern table pieces as there were apparantly no Alaska shakers. These are often identified as “Fluted Scrolls,” “Klondyke” (Northwoods), and concurrently, “Alaska.”

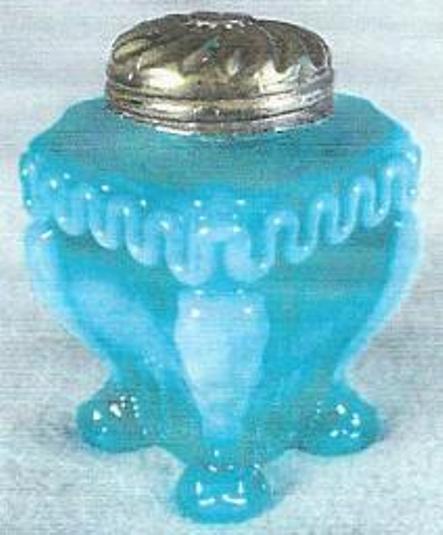

The newly found Northwood Alaska shaker on the left – Northwood’s Klondyke/Alaska shaker on the right

The Klondyke/Alaska shaker happens to sometimes have a decor that is seen on the Alaska table pieces, no doubt leading Heacock to surmise that the Klondyke shaker was intended to be used with both the Klondyke and Alaska tableware. We will never know if this was truly the case because the Alaska table pieces were square in cross section but often had the decor seen on the Klondyke/Alaska shakers. Additionally, until recently no shaker with a shape like the Alaska pattern had been reported. Now, shown above, left, is an undecorated opalescent blue Alaska salt shaker. The design matches that of the Alaska table set pieces. Now the question remains why no other shakers in this design have surfaced to date. This has to mean that the production was very limited or made for a special purpose, as other pieces of the Alaska pattern are frequently seen. This rarity for the shakers, coupled with the Alaska matching decor on the Klondyke shakers, causes one to assume that although the expensive mold had been made, Northwood chose not to use it in full production. One would surmise that production costs were just too high for these shakers.

The shaker above, as well as the other pieces of the pattern, are pressed. The photo shows the center section of the shaker is where the plunger was inserted and removed. Since the plunger was round in cross section and the shakers square, the glass is thick at the corners. This likely caused high production costs. Either production failures or extended cooling or annealing times for the glass were required. Whatever the case, it must have been significant, as Northwood would not likely have given up so easily. Because the shakers are so beautiful and match the table set pieces, they would indeed have enhanced the sales of this pattern.

It is difficult to know why certain techniques were used at the time, and why certain decisions were made, because production techniques were so primitive by today’s standards. The cost of production was significant and the available approach was selected based upon factors we may not understand today. However, it seems that the original design concept for the mold would indicate potential problems for pressing. Perhaps it is second guessing, but it seems the design would be much more suited to a blown mold approach. It is unfair for us today to second guess the genius of Northwood, but we have to believe that there was a very good reason.

References: Heacock, Measel, Wiggins, “Harry Northwood, The Early Years”, Antique Publications, 1990 and Heacock, “Victorian Colored Pattern Glass, Book 6”, Antique Publications, 1981.